The Carriage Barn Arts Center has opened the first retrospective exhibition highlighting the late Pulitzer-prize winning photographer Edward Keating’s 40-year career, as well as his connection to New Canaan. “A Fearless Legacy” runs through Nov. 13.

We put some questions about Keating and his work to Carrie Boretz, a photojournalist and Keating’s wife of 33 years.

Here’s our exchange.

***

New Canaanite: Edward Keating was an important photographer at the New York Times and elsewhere. For those who may not know him or his work, please give us a brief overview.

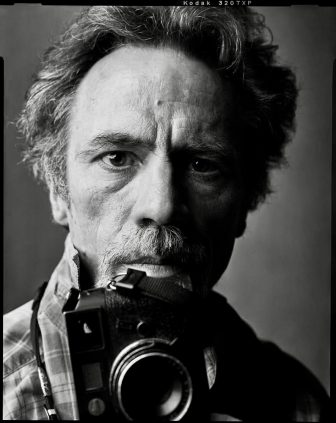

Photo of Edward Keating by Mark Seliger

Carrie Boretz: Edward Keating began his career in his mid-twenties while attending Columbia University, after a few stops and starts. After buying his first camera, one roll of film later he knew this was the career for him. He began soon after shooting for the Columbia Spectator. After leaving the university, he started driving a taxi at night so he could start shooting during the day. He began to also assist established photographers such as Mark Seliger and Peter B Kaplan. He went back to live in New Canaan, the town he grew up in to work at the New Canaan Advertiser for a few years covering town events and news. He started freelancing for magazines such as Forbes and Business Week and in the late 1980’s he began almost full time shooting for the New York Times.

After almost getting killed while covering the Crown Heights riots in 1991, they offered him a full time job. He soon took off there having much influence with his style of shooting. He covered everything. from hard news to weddings and became the Style sections main photographer for their VOWS section. He was assigned often for the NY TIMES magazine, going to Vietnam with the noted war reporter Tim O’Brien to documenting Route 66 in its entirety. He left the Times in 2002, after winning two Pulitzers shared as a member of the photo team. He spent months and months at ground zero, staying in the pit and its surroundings, day in and day out and was quoted as saying it was part of his responsibility to cover the aftermath.

What are Keating’s ties to New Canaan? Why did the Carriage Barn decide to put this exhibition together?

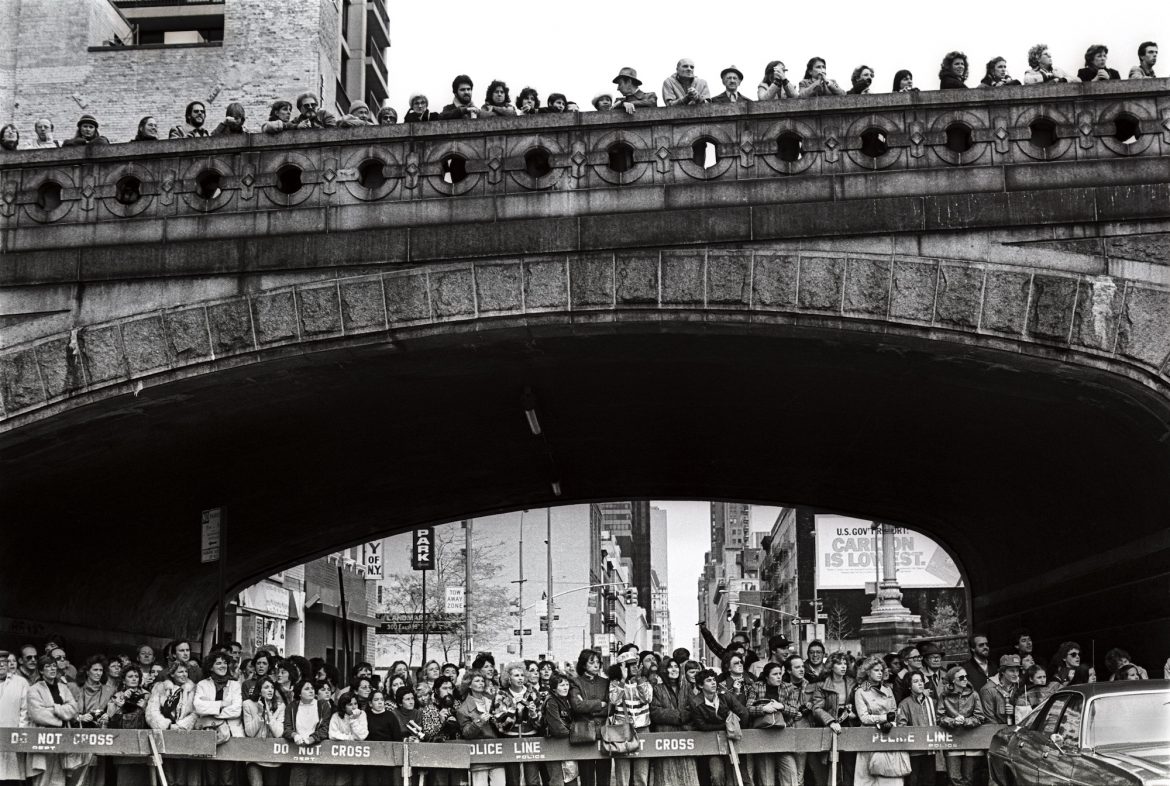

Edward Keating photo. Courtesy of the Carriage Barn Arts Center

Eddie was born in Greenwich, Conn. in 1956 and grew up in New Canaan. Losing both parents by the age of 14, he felt much allegiance to his friends and their families with taking him into their care in addition to his older sister who took over the responsibility. He never forgot this and throughout his adult life went back often to visit. At the invitation of Jeanne McDonagh, former head of the NCHS art department, he served on the committee of the Fritz Eager Foundation for many years and as a mentor to photography students.

After leaving the Times, he joined Contact Press Image and freelanced often for Time, Rolling Stone, New York Magazine, Popular Mechanics. and Vanity Fair. He spent the next 15 years shooting Route 66 before publishing his book, “Main Street: The Lost Dream of Route 66,” published by Damiani in 2018. Exhibits from this series have been at the Nailya Alexander Gallery on 57th street, NYC, the Leica SF Gallery. Since his passing in 2021 it has traveled to Tulsa, Ok, Chicago, LA, and over the next few years in Santa Fe, Flagstaff AZ, Amarillo, Tx, and St. Louis, MO. This was one of his dreams. to show the 66 work along the route.

Edward Keating photo. Courtesy of the Carriage Barn Arts Center

I wanted to bring his work back to his hometown and contacted Hilary Wittmann at the Carriage Barn Arts Center over a year ago about organizing an exhibit. Many of these photographs have never been shown before, and some that were found on undeveloped film rolls he never saw himself. Eddie was more into the process of shooting than examining what he shot. It’s so important to me and our daughters to shine a light on his work and continue his legacy he worked so hard creating—partly with his sharp instincts and his endless ruminations concerning his craft.

Keating’s work was described in his NYT obituary as juxtaposing “harshness and delicacy.” Tell us about the exhibition itself. How many photographs are there? How would you describe their range and style?

Edward Keating photo. Courtesy of the Carriage Barn Arts Center

The show’ title “Fearless Legacy” describes Eddie’s courage and determination as to how he saw and felt and in capturing the most he could out of any story. To see what was before him as fully as he was allowed, even risking his life. In 1991 Eddie covered the Crown Heights riots as a freelancer for the New York Times and got attacked by a mob of around 100 teenagers. They not only took all his cameras, but put a brick through his head and almost killed him. In the late 90s, he covered the The Serbia-Kosovo War. One day he crossed the border into Serbia to shoot the refugees. He wanted to get a unique angle, other than how other photographers were shooting it. He was taken by the Serbian cops, dragged into an office for hours, put a plastic bag over his head with a gun pointed at his head. After many hours they found his harmonica which he always carried with him in his camera bag. They started jabbing him in the ribs with it and started demanding he play Bob Dylan. He couldn’t believe what he was hearing, but of course did what they said and began to play a beautiful rendition of “Mr. Tambourine Man” with his eyes closed knowing he was playing for his life. He opened up his eyes and tears were rolling down the cheeks of the Serbian police and they said “OK get out of here” and offered him a cigarette.

Edward Keating photo. Courtesy of the Carriage Barn Arts Center

Keating’s Pulitzer is connected to his work with the Times in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Are any of those photos featured as part of this exhibition? How did the Carriage Barn gain access to his work?

At Ground Zero he wanted to bring back pictures that no one else was shooting, and he did. One day soon after 9/11 he saw an elegant tea set covered in ash, in an apartment nearby to the pit, a poetic image in the midst of all that horror. This image helped win the Pulitzer for the paper and is in the show in New Canaan‘s Carriage Barn. He passed away 20 years later because of the toxic materials he continually breathed in for months.

Edward Keating photo. Courtesy of the Carriage Barn Arts Center

The edges of Eddie’s frames were as important as the center. Often a myriad of details that the viewer has to keep returning to see it all. Content and composition being of equal importance. Using a Leica as he did throughout his career, he saw exactly what was before him through his mirrorless camera. Because they were quiet cameras, his subjects often had little idea of what he was capturing. Keating was quick on his feet and with his sharp eye, huge heart and masterful skills, we can now appreciate all he gave to his art.

Looking forward to a pleasing view.

I met Ed Keating when he was a student at NCHS in the early Seventies. He was a one-of-a-kind human being, who always marched, with total integrity and situational independence, to his own drummer. His humanity was deep, his talent was singular, and his selfless legacy will endure through the lens of his Leica. Thanks, Ed.