New Canaan’s charm and specifically its historic character—a sense of protected heritage that could be seen in both private homes and natural landscape—attracted preservation architects Carl and Rose Rothbart to town when they moved here 20 years ago.

In fighting for preservation of the Jelliff Mill structure and historic home up the hill nearby, Carl and Rose Rothbart opposed development plans at 41 and 47 Jelliff Mill Road.

Since then, the pair said they’ve seen that defining quality of New Canaan change dramatically, due at least in part to developers who “strip-mine” (Rose’s term) real property here through teardowns and new construction, or in many cases, subdivision.

The feeling that drew the Rothbarts to town has nearly vanished, Rose— current president of the New Canaan Preservation Alliance, a nonprofit group—said during an interview in her husband’s Pine Street office on a recent afternoon.

“It’s getting close to being lost entirely,” she said. “It happens gradually. So sometimes people don’t get it. People don’t see it. But we see something and we just enjoy driving past it. We enjoy having it part of our lives, and appreciate the historic contribution and physical contribution that it gives to the town.”

The sentiment is captured by a change this month at Jelliff Mill that Rose and Carl have felt deeply.

The home at 41 Jelliff Mill Road, which preservationists and historians date to the early 18th Century, has been demolished.

In the past two weeks, they watched as one historic home—41 Jelliff Mill Road, a structure that appears to be referred to in 1755 and may date even earlier, well ahead of the American Revolutionary War (and so at least a full generation before New Canaan’s incorporation)—was torn down. A 10-unit development called “Jelliff Mill Falls”—which name, they say, is at least an ironic twist if not a deliberate poke at those who have been fighting for several years to spare from the wrecking ball the house and attendant mill structure at No. 47—is quickly going up on the site. (Half of the units are under contract—a shining success in what some local Realtors have called a largely ho-hum market.)

162 Woodland Road, on the corner of Main Street. A 1934 home came down in Feb-March 2014 and a new home triple its size is going up. Credit: Michael Dinan

For the Rothbarts, the demolition where Jelliff Mill Road crosses the Noroton River is a striking example of this type of loss for New Canaanites. Main Street is an example of a town road that’s seen many of its historic homes torn down, Rose said.

“One after another, there are these ancient houses—really very historic homes and architecturally important homes—and just one after another, they just go down and are replaced by some cookie-cutter thing that has no intrinsic value,” Rose said.

Jelliff Mill in Recent Years

The Jelliff Mill property—sold in December for a total of $3 million between numbers 41 and 47, according to tax records—for years has been at the center of lawsuits involving the property’s former owners, neighbors and the town. When plans emerged for development there and initially were denied by Planning and Zoning, the owners fought that decision while some neighbors filed suit arguing that the town’s denial should’ve been made on different grounds.

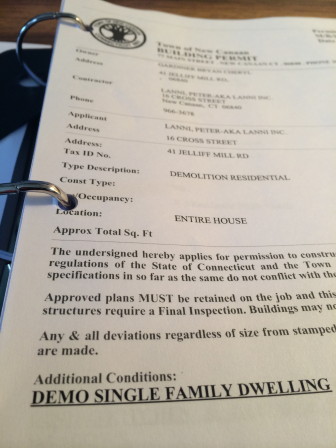

The demolition permit for 41 Jelliff Mill Road.

Soon, a plan for building emerged that would’ve seen developers cite a state law that would allow them to skirt certain local planning decisions. (Essentially, for municipalities whose affordable housing stock—as the state defines that term, and it derives from data such as rent or house payments relative to median income for the region—is below a certain level, a new complex that sets aside a certain percentage of units as affordable can qualify for approval.)

Eventually, an agreement was reached whereby developers paid the town $200,000 toward affordable housing and proceeded with construction, the Rothbarts said. A New Canaan resident and former property owner who has spoken to local media outlets in favor of the modified design could not be reached for comment.

Construction is happening now, though the mill and historic home at Jelliff Mill have been registered for about two years with the Connecticut State Register of Historic Places. The designation itself doesn’t spare a building from demolition, the Rothbarts said. One way to at least slow down the process for review is to take on the very difficult task of getting a Historic District designation for an entire neighborhood—New Canaan already has one all around God’s Acre—and that among other things involves getting a percentage of homeowners in an area to agree, the Rothbarts said.

Historic Jelliff Mill

The area around Jelliff Mill ranks among the earliest to be settled by colonists in present-day New Canaan.

Here's a panoramic photo of Jelliff Mill during construction, in April 2014.

“New Canaan broke off from Stamford—Stamford is one of the oldest communities in Connecticut—and New Canaan decided they wanted to have their own parish,” Rose said. “They broke off. This particular area, along with the original mill, was one of the first original communities. There was a little store there. There were several houses—some of them still exist—that were in that little area. It was a neighborhood.”

The 2.5-story, Federal-style house east of the mill with its gable roof and brick chimneys, long had been part of that neighborhood.

To do justice to it, a fuller history of the property, part of the state registry application—researched, written and provided to NewCanaanite.com by Rose and fellow New Canaan Preservation Alliance member Mimi—follows this article.

Here are some bullet points on the house, dam and mill:

- No record of original dam construction;

- Mill on Noroton River mentioned as early as 1718;

- Existing stone dam said to have been constructed approximately 300 years ago, and appears to have been built together with an original mill building dating to 1744;

- A house is believed to have been built by David Stevens next to the dam in 1714, as per 1930s WPA architectural survey of New Canaan;

- Talmadge family sold mils and house for $500 to Deodate Waterbury of Darien in 1801 (the year of New Canaan’s incorporation);

- Waterbury Mills property sold in 1869 to Aaron Jelliff, Jr. of Wilton;

- Mill operated as grist, saw and planing mill, later a sieve factory;

- Most recent concrete block mill building dated to 1949;

- George Jelliff III sold C. O. Jelliff & Co in 1967 to the Railroad Avenue Corporation which made shipping boxes;

- Large waterwheel survived until 1972, when it was washed away in a hurricane. The mill was sold to the New Canaan Lumber Company in 1988, continued to produce custom millwork with architect George Lounsbury working there.

Rose said that the way the home was built and developed by its owners through centuries was “incredibly unique.”

“He [Deodate Waterbury] had a little closet off of the main room. Right off of his main room there was a huge fireplace there, with a massive stone foundation to it, and right off of it was his little closet and he started a little store. You had your community, neighborhood stores that people walked to.”

The mailbox at 41 Jelliff Mill Road, a home that New Canaan preservationists say was historically significant, has been removed from the construction site there, where 10 units rapidly are going up.

For the Rothbarts, the tearing down of what they call the Stevens-Waterbury-Merritt House is an irretrievable loss of local history.

“Once you obliterate it—especially obliterate it, just totally redesign the physical layout of the area—you have no concept of it any more. You don’t know it was there,” Rose said. “You don’t know what the story is.”

For the Rothbarts—though it may have been intended as a nod to history—that the individual units in the new Jelliff Mill Falls complex are named for some of the area’s early settlers (a look at the building permits in the tax records shows they’re called, variously, “Waterbury House,” “Stevens House,” “Talmadge House” and “Aaron Jelliff,” among others) feels overwrought, a kind of twisting of the knife for preservationists seeking to save 41 and 47 Jelliff Mill.

This pile of rocks is what was left of the foundation at the 41 Jelliff Mill Road site just a few days after a demolition crew took it down.

“You cannot replicate this sort of thing,” Rose said. “What I feel we’ve lost, it’s something I can’t necessarily put into words. It’s something you feel. It’s an experience.”

***

Here is the full Narrative Description of the “Jelliff Mill Historic District,” prepared by members of the New Canaan Preservation Alliance for Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism’s Historic Preservation and Museum Division/State Historic Preservation Office, as part of an application for state historic registry designation (subsequently approved—footnotes follow, we don’t have the photos and maps referred to within):

Located beside the Noroton River in the southwest region of New Canaan, CT originally part of the Town of Stamford, this property was once part of a larger parcel of land that has changed both hands and boundaries through the years. Before Europeans settlement this area Native Americans inhabited the property as evidenced by artifacts which were found by previous owners, and are now housed at the Stamford Museum and Nature Center.[1] These two buildings are sited on the gently sloping southeast bank of the Noroton River in the Talmadge Hill area, also labeled as “Millville” on some historic maps (MAP 3), of New Canaan.[2]

Jelliff Mill Road runs primarily east to west (PHOTO 44) connecting Old Stamford Road, which had been known as Stevens Street an extension of Hoyt/Weed Street in Stamford on early maps (MAP 1), on the east with Ponus Ridge Road on the west in the Southeastern region of New Canaan. The house is parallel to the road facing south (Photo 2).

The mill building (#47 Jelliff Mill Road) sits adjacent to and at a right angle to the small dam at the southern terminus of the mill pond (MAP PAGE 9). This concrete block building with a low-sloping gable roof was constructed in 1949 and was built on the site of the original mill building which records date back to at least 1744. Portions of the existing building were constructed on the footprint of the original mill building. ( MAPS PAGES 6-7)[3]. The mill building is sited so that it is one story on the northwest, northeast and southwest facades which are adjacent to the up hill slope and two-stories on the southeast facade which is adjacent to the river. The building has an industrial, functional appearance, with large industrial steel windows on all facades. The mill building is oriented parallel to the road as it curves around the property and the waterfall. The property is primarily composed of open grass-covered lawn bordered by deciduous trees with a few evergreen shrubs as accents and a small group of white birch trees on the river bank of the mill lawn.

Jelliff Mill Dam is located at the Northwest corner of the Jelliff Mill building and extends out to the west approximately another 50 feet until it becomes embedded in the earth embankment on the west. The northwest and southwest foundation walls of the mill building serve as part of the dam structure (Photos 45 and 47)[4]. Directly adjacent to the building was the wheelpit, the flanking wall of which can still be seen.

The house (#41 Jelliff Mill Road) is located to the east of the mill, a little further up the hill from the mill pond. It is a two-and-one-half story, gable-roofed, clapboard-clad, Federal-style building. A one-story, shed-roofed addition extends along the entire west elevation. A two-story ell with a gable roof extends from the northeast half of the north elevation. Two brick chimneys are symmetrically located along the north wall, but set behind the roof ridge.

At the house a fieldstone retaining wall borders Jelliff Mill Road which serves as the southern border for the property (Photo 2). This fieldstone wall continues up the east side of the driveway (Photo 1). A large portion of the property adjacent to the mill is covered by a paved driveway along the northwest façade of the building (Photos 32, 36 and 37)[5]. On the southwest façade, the Noroton River continues along its course after cascading over the stone and concrete dam, past the concrete block façade of the mill building with its stone foundation and the stone retaining wall for the lawn beyond (Photos 42 and 45). Visible in the rocky riverbed are large boulders and the stone piers which supported a footbridge (Maps 5 and 6).[6] The Noroton River immediately passes under the bridge for Jelliff Mill Road which serves as the southern border for the property.

Located just northeast of the house is a modern garage structure which replaced an older though not historic structure (Photo 6).[7] The footprint of the mill building is primarily rectangular running southeast to northwest with a square ell extending to the southeast towards the dam. Two smaller additions have been added, one from the northwest elevation and one from the northeast elevation. A small building was located across the river from the main wooden mill building and was accessed by a footbridge which washed away in 1955. The stone support piers of this footbridge can still be seen (Photo 42). A smaller rectangular shed was located to the north of the mill building as seen on the Sanborn maps of 1906 and 1912 (MAPS PAGES 6 and 7).[8] In some local historic documents it has been written that this structure was constructed on the foundation of an older structure which was moved up the hill either as it existed or dismantled and rebuilt to become Mr. Waterbury’s house.[9] This theory has not been verified to date. Also visible on the 1906, 1912, and 1927 Sanborn maps is another mill-related structure across Jelliff Mill Road.[10]

Jelliff Mill

As Jelliff Mill Road dips to curve around the mill and waterfall it turns in a southwesterly direction and the façade of the mill building is oriented parallel to the road as it turns. This southeast façade has two double, fifteen-light windows symmetrically arranged on the façade with the ghost of a doorway between them (Photo 32). Setback, to the east is a small addition with a garage door (Photo 38)[11]. To the west is the setback southeast façade which has two stories exposed as the land drops down to the river with a small six-light window at the west corner, and continuing across the setback elevation are two doorways and a small shed-roofed addition (Photo 42). On the second floor of this setback elevation are two double, twelve-light windows.

While the first floor of the southwest setback elevation has no windows or doors there are two double, fifteen-light windows on the second floor (Photo 33). The Noroton River flows at the base of the southwest main elevation which has a symmetrical arrangement of windows with two small, six-light windows on the first floor and two double, fifteen-light windows on the second floor. A small, brick chimney is located just slightly right of center between these windows. On the north, southwest setback elevation is one large, twelve-light window and two small two-light windows.

There are four windows on the northwest elevation, one double, fifteen-light, and two twelve-light windows on the main elevation, and one single, twelve-light window on the extension at the north corner (Photos 34 and 35)[12].

Along the northeast elevation are a series of windows and doors beginning with a double, fifteen-light window at the south corner, the blank wall of a shed-roofed addition, another double, fifteen-light window, a door, two garage doors, a small six-light window, a door, and another small, six-light window (Photos 36, 37, and 38)[13].

Jelliff Mill Dam

The existing stone dam which served to create Jelliff Mill Pond and power the adjacent grist and saw mills is said to have been “constructed approximately 300 years ago”[14] appears to have been built in conjunction with the original mill building which can be dated to 1744.(Photos 44 – 49) This solidly constructed dam made by colonial artisans of local rock and boulders and backfilled with solid earth has held the waters of Jelliff Mill Pond for many storms and powered the endeavors of the industrious and inventive minds of the various owners of the adjacent mill over the centuries. Observing the rate of water flowing over the spillway and crashing onto the rocky stream below has been used by locals as a measure for the strength of many storms or the rate of snow melt in Spring. The waterwheel which operated in its wheelpit was still in place until a hurricane in 1972.(Photos 28, 30,31)

Talmadge-Waterbury-Merritt House

The house is sited facing south on a hill overlooking Jelliff Mill Road with its gable roof running east to west and parallel to the road (Photo 2)[15]. The façade is five bays wide with a central entry flanked by narrow three-paned sidelights located slightly off center towards the east with a small one-story, shed-roofed porch with simple square columns (said to have been “chamfered” in the WPA Architectural Survey)[16]. Windows throughout are mostly six-over-six double-hung sash with plain trim.

On the north elevation, there is a single window, a shed-roofed addition and an exterior chimney (Photo 4).[17] Just to the east of this chimney is a doorway leading into the back of the first floor central hallway. Prior to renovation a small open shed-roofed structure which extended beyond the exterior chimney provided shelter at this doorway, but since renovation the structure was narrowed so that its width only extends up to the chimney and it has been enclosed. On the second floor are two windows symmetrically arranged on the west half of the façade and two additional windows just to the east of the exterior chimney.

Extending from the northeast half of the north elevation is the ell whose gable roof runs south to north. According the the WPA Architectural Survey this ell was constructed circa 1850[18] The west elevation has two windows on the first floor and one on the second floor. Centered in the north façade, first floor is a single eight-over-eight double-hung window which replaces two typical windows (Photos 4 and 9).[19] There are two typical windows symmetrically arranged on the second floor of this elevation. The first floor, east façade of the ell has one typical window towards the north end of the façade plus one large twenty-eight pane fixed window towards the south end of the façade which replaces two typical windows (Photos 5 and 9).[20] Two small double-hung, four-over-four windows are evenly spaced on the second floor of this elevation.

This is a house which has evolved over time and whose history is mired in local tales. Information in the WPA Architectural Survey which states that the west two-story portion of the main body of the house was the original core of the house[21] is born out in architectural clues found within. Photographic evidence during the 1987 renovation shows the exterior of the house with its shingles removed. Visible in the photo is the front girt on the west end of the house (Photo 10).[22] This evidence in combination with the fact that the west side of the house is wider than the east side point to two different phases of construction. Other photos reveal that portions of the house were constructed of heavy timbers and that scribing of these timbers was employed during construction (Photo 26).[23]

Interior

Currently two rooms with a central hallway on the both the first and second floors make up the main body of the house. On the first floor, in the west room referred to as the “keeping room”, is the large stone cooking fireplace, typical of the Colonial period with its brick beehive oven situated along the wall to the left (Photos 11 and 12). Simple, flush Horizontal paneling created a wainscot along the walls and the majority of the moulding in this room employed plain flush boards. Between the widows on the south wall is a built-in desk referred to as a spice cupboard in some notes from the 1987 renovation (Photo 13).[24] In the basement below the keeping room is the massive stone foundation for this fireplace (Photo 14).[25] A single flight of stairs with a simple, Federal-style newel post and railing with square balusters runs along the east wall of the central hall (Photo 15).[26] Horizontal, flush board wainscoting noted to have a beaded detail in the WPA Architectural Survey,[27] is found along the walls of the central hall. This architectural feature indicates that the hallway was part of the original core of the house.

East of the central hall is the parlor which appears to be part of the second phase of the house (Photos 17 and 18).[28] This room features a much smaller stone fireplace with a finished soapstone surround framed by a neoclassical mantle. In contrast to the horizontal wainscot in the other rooms, the parlor features a moulded chair rail. Doors symmetrically arranged on either side of the fireplace are four paneled and framed with moulded door cases.

West of the keeping room on the first floor is the shed-roofed addition which is accessed through a door centered on the west wall of the keeping room. This room’s purpose and the date of its construction are not known. Perhaps this is the structure which legend states was moved up the hill from near the mill pond?

On the second floor of the main body are two bedrooms separated by the central hallway on the north and a small room to the south above the stair. In the west bedroom, which is believed to be part of the original core, is a small stone fireplace with a large granite lintel (Photo 19).[29] Flanking this fireplace to the left are four small cabinets built into the wall which itself steps in and out about the fireplace. On either side of the fireplace are narrow plank doors which provide access to a storage room or closet which wraps around behind the fireplace and has its own windows on the north wall of the house. Located slightly less than halfway up the west wall is a large horizontal beam spanning the width of the wall and terminating at a two-part corner post at the south wall (Photo 20)[30]. This construction detail indicates an alteration in the room height. Also the change in the thickness of the south wall supports the legend that when Deodate Waterbury moved into the house in 1801, he “raised the roof” of the existing structure in addition to enlarging the house. In contrast, the bedroom to the east of the central hall employs a Franklin stove for heat and has a pair of four paneled doors symmetrically flanking the stove (Photo 21) .[31] One enters this room from the hall through a small vestibule to the left and behind the chimney. This vestibule also has a door which provides access to the second floor of the ell. To the right of the chimney is a closet. A simple chair rail adorned this bedroom and the corner posts extend from floor to ceiling in a single unit indicating that no alteration has been made to the height of this room (Photo 22)[32].

On the first floor, the ell is accessed via a pass-through to the east of the parlor chimney in the thick chimney wall or through a doorway at the back of the central hall under the stair. In the ell, which is considered to be a later addition circa 1850[33], is a single brick fireplace behind the parlor fireplace in what is now called the great room. An enclosed winding stair, with a small closet underneath, once stood in the northeast corner of this room providing access to the floor above (Photo 23)[34]. A large kitchen to the rear of the first floor now occupies what once were two smaller rooms. On the second floor the stair came up into a large, square hall off of which three sloped-ceiled bedrooms were located. (Photos 24 and 25)[35]

Although the entire façade is currently clad in clapboards, photographic evidence from a renovation in 1987and the WPA Architectural Survey, indicates that the façade was previously clad in wood shingles (Photos 7-9, and 27).[36] Currently, the roof is clad in asphalt shingles. A fieldstone foundation creates a basement and is just visible at the base of the house. A massive stone foundation with wood beams supports the large fireplace in the keeping room above. The interior of the fireplaces are composed of local soapstone and the mortar is said to be composed of the oyster shell mortar that Deodate Waterbury produced in his adjacent mill.[37] In the keeping room, above the large fireplace is a wooden beam at the sloped ceiling with a chain whose purpose may have been to facilitate lifting heavy cooking pots. To the left of the large fireplace is a beehive oven. In the more formal parlor the fireplace surround is finished with soapstone quarried from the banks of the Noroton River itself. This parlor mantle is a neoclassic Federal style as is most of the moulding in this room. Most of the trim in the remainder of the house is much simpler, basically having no particular style. Doors run a variety from utilitarian flush-boards on the closets, to a heavy six-panel Colonial-style with iron hardware on the front door (Photo 16),[38] to the more high-styled four-paneled doors in the parlor.

In the “keeping room” and the central hall downstairs the base of the walls were clad in wide flush horizontal boards. An interesting feature of the house is the positioning of the chimneys away from the north wall which creates a space allowing closets around the chimney and pass-throughs into the rooms and to the ell on the east end. In the keeping room the north wall angles out diagonally from the large fireplace then returns flush creating a large closet with a small window. This closet is believed to have been used for the general store that the Waterburys operated first out of the “keeping room” itself before they later constructed and operated a general store on the corner of Jelliff Mill Road and Old Stamford Road.[39]

Both buildings and the dam are in good condition and have retained significant character. The 1949 mill building is a replacement for a building which has stood on the site at least as early as 1744. Industry continued in this building until 2004. The mill building and its dam as well as the house are an integral part of an area which centered on the Noroton River and was once teeming with activity (PHOTO 44). The mill building was the central building of a complex of buildings on this site and several other locations along the Noroton River which were constructed by the Stevens family, Thomas Talmadge and his family, Deodate Waterbury and his family, and the Jelliff family.[40] Various operations were performed in these various structures, all but the remaining mill building have been demolished, deteriorated or burned. Jelliff Mill and Dam and the associated Talmadge-Waterbury-Merritt house are the few structures remaining to give testament to the history of this once vibrant community.

[1] Joan Ready and Betty Harding, Site Survey pertaining to Pre-History of New Canaan, 1980, pp. 6, 7. Picture 1. From the files of Ernest Wiegand, Norwalk Community College; artifacts at the Stamford Museum.

[2] Atlas of New York and Vicinity. New York: F. W. Beers,

[3] “New Canaan, Connecticut.” 1906, 1912. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1867-1970 – Ohio

[4] 2011 Municipal Inland Wetland Commissioners Training Program Segment 2. Connecticut’s Inland Wetlands and Watercourses Act. Wray v. New Canaan Inland Wetlands & Watercourses Comm’n, 2011 Conn. http://www.ct.gov/dep/lib/dep/water_inland/wetlands/seg2_2011ag_outline.pdf. 2-27-12

[5] Town of New Canaan, Planning and Zoning Website, Application of 47 Jelliff Mill LLC, 1/24/2012

[6] “New Canaan, Connecticut.” 1906, 1912. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, Ibid.

[7] Anka Jones, Photographs from 1987 Restoration

[8] “New Canaan, Connecticut.” 1906, 1912. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, Ibid.

[9] Mary Louise King, 41 Jelliff Mill Road, 1996 typed mss in NCHS files “Jelliff Mill House”; Robert Dean, Project Memorandum, 1/24/2012; Mrs. Robert D. Dumm, “The Stevens-Waterbury-Merritt House”, Landmarks of New Canaan, New Canaan Historical Society 1951, p 319-320; Town of New Canaan, Property Appraisal Website, http://appraisalonline.newcanaanct.gov:8080/search.php, 2/1/2012

[10] “New Canaan, Connecticut.” 1906, 1912, 1927, 1949. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1867-1970 – Ohio.

[11] Town of New Canaan, Planning and Zoning Website, Ibid

[12] Town of New Canaan, Planning and Zoning Website, Op. Cit.

[13] Town of New Canaan, Planning and Zoning Website, Op. Cit.

[14] Town of New Canaan. Planning and Zoning Website. Zoning Application. “Connecticut DEEP Dam Repair”. Permit Application of 47 Jelliff Mill LLC: 12/21/2011

[15] Anka Jones, Ibid

[16] Connecticut State Library. WPA Architectural Survey. “New Canaan historic building 012”, 1935-1942

[17] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[18] Connecticut State Library. WPA Architectural Survey. Ibid.

[19] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[20] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[21] Connecticut State Library. WPA Architectural Survey. Op. Cit.

[22] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[23] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[24] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[25] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[26] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[27] Connecticut State Library. WPA Architectural Survey. Op. Cit.

[28] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[29] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[30] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[31] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[32] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[33] Connecticut State Library. WPA Architectural Survey. Op. Cit.

[34] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[35] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[36] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[37] Mrs. Robert D. Dumm, “The Stevens-Waterbury-Merritt House”, Landmarks of New Canaan, New Canaan Historical Society 1951, p 320.

[38] Anka Jones, Op. Cit.

[39] Anka Jones, Op. Cit. ; Mary Louise King, Op. Cit ; Carlton Hill and Mrs. Robert D. Dumm, “Jelliff Mill Memories”, Landmarks of New Canaan, New Canaan Historical Society 1951, p 281.

[40] “New Canaan, Connecticut.” 1906, 1912, 1927, 1949. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1867-1970 – Ohio

Great article! I still confess though that I don’t understand the whole business of the payment of 200,000 to the town. I can understand the need for low and middle income housing and would have welcomed any addition to the town’s stock; yet 200,000 will barely get you a foundation in New Canaan. How does a minuscule payment to the town equate to the provision of entire units at the site?

Totally agree. This project was approved because of affordable housing goals. At the end of the day, though, no affordable housing goal was met. Now another developer can again have a project approved regardless of demolishing buildings of historical or town significance. What does that $200k go towards?