Charles Robinson, owner and resident of one of New Canaan’s oldest and most prominent homes, has a ready analogy to explain the philosophy that he and his wife Sarah embrace as they make improvements to their property.

New Canaan’s Charles Robinson stands in the area of his barn’s foundation at 4 Carter St. If the town approves a Special Permit application, a re-assembled antique barn now laying in pieces (mostly on the Robinsons’ property) will go up where he’s standing. Credit: Michael Dinan

In the nearly 20 years that the Robinsons have owned the 1737-built classic Connecticut saltbox at 4 Carter St.—long known to scores of New Canaanites as “the pumpkin house,” for its former painted color when clapboarded—the couple has taken great pains to respect the antique’s craftsmanship, heritage and aesthetic, preserving and achieving a harmony and consistency with the home that Charles refers to as “consonance.”

“Let’s say you are given a Bentley and it is a 1968 Bentley, the real deal, and it comes with all its flaws but there is also the original leather and handcrafted Bentley engine and all the panels are hand-beat it has been painted with real lacquer,” Robinson said on a recent morning, standing in a clearing on the south side of his property where, until last year, an irreparably sagging barn had stood. “When you have that and you are going to go to put new tires on it, instead of just saying, ‘I am going to go down to Mavis Discount Tire,’ you will stop first and say, ‘I at least better find out what kind of tires were original, and does it pay to do that from the standpoint of value, or am I better off from a safety and utility perspective to get radials and, if so, what radials?’ When you have something that is genuine and you know it is valuable, you stop before you just go paint it pink. You catch yourself and say, ‘With every move I make, I can hurt this if I do not do it as close to right as possible.’ ”

If approved by the town, a workshop addition at the back of the “new” (re-assembled) barn will look toward the south at the New Canaan Mounted Troop, and through windows that were salvaged from the Mounted Troop itself when the organization’s indoor riding rink was demolished. Credit: Michael Dinan

With that in mind, the Robinsons on Tuesday night will seek a Special Permit from the Planning & Zoning Commission that, if granted, will see them erect with some slight modifications an antique barn from Hancock, Mass., that they purchased and had disassembled and which now sits in a weather-protected pile in their yard.

Technically, the permit they’re seeking is for a detached “garage” that will exceed 1,000 square feet—see page 53 of the regulations here. The Robinsons last month won approval 5-0 from the Zoning Board of Appeals for a variance regarding the structure’s height (Charles calls it “the Hancock barn”) that also was needed for the project.

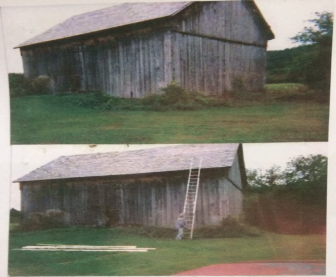

The original barn, now razed, at 4 Carter St.

If approved, the “new” barn installation—supported by historic preservationists and neighbors alike—will mark a unique and widely anticipated addition to a storied New Canaan property whose owners distinguish themselves as both passionate and practical stewards.

Images of the “Hancock” barn shortly before it was dismantled.

In explaining his sensitivity to what local historians have dubbed “The Fitch-St. John-Ruscoe House,” Charles readily runs through his practical reasons: The house itself is more valuable is care is taken in its preservation, including through updates, the family very much wants more storage and a functional car garage (“We’re tired of digging out in the wintertime) and—with respect to a workshop that the Robinsons plan to add to the Hancock barn—they want a nice space to pursue hobbies that include pottery (“It’s more fun to work in a shed or barn than in a basement”).

And this is how Charles describes what he and Sarah have accomplished so far, with the help of a gifted housewright and others: “We’re not so smart. We just copy.”

New Canaan’s Tom Nissley found this painting at a tag sale up on Canoe Hill Road. Two women, schoolteachers who had been born and lived their whole lives in New Canaan, painted the home at 4 Carter St. when it was clapboarded and painted a pumpkin color—known locally as the “Pumpkin House.” The painting hangs in the Robinsons’ house, in a room of the original 1737-built structure.

“We get something that is—if not exactly alike—then as close to like the house as it can get. And what we have learned is if you do this copying thing, it is hard to screw it up.”

In the case of the Hancock barn, “just copying” involved carefully disassembling the structure in a sort of reverse-construction process—siding, then roof shingles and sheathing boards, rafters and then major beams and posts. With approval from the town, re-creating the Hancock barn on Carter Street will involve erecting the timbers and rafters of the barn (including with “long sticks,” 38-foot long beams that are being stored in Sheffield, Mass.) to create the skeleton, while also using some hewn timbers the Robinsons own in order to create the workshop addition to the roughly 38-by-38-foot barn—a workshop that will face the paddocks of the picturesque and neighboring New Canaan Mounted Troop, through windows that themselves were salvaged from the organization when its indoor riding rink was demolished.

Here’s one interesting view from inside the Robinsons’ home, taken from the modern “addition and looking back into the original house. The door on the left marks the start of the addition. Beyond it is the kitchen and important gathering area in the original 1737 home. Credit: Michael Dinan

“In plain English, we will be making—from native hewn timbers sourced previously by Sarah and me for a house project—our housewright will be fabricating, cutting mortises and tenons to add the shed addition onto the Hancock barn frame,” Charles said. “And then what will occur is a skinning process, starting with the roof and working down in terms of siding, and in our case there are going to be cedar shakes of siding as we did with the house.”

It’s a project that has earned wide support.

“These guys are going to make this barn something that everyone is going to want to look at,” town resident Cindy Hagopian said at the Aug. 3 ZBA meeting, speaking in favor of the Robinsons’ application for a variance.

An example of a mortise and a tenon, a hand-hewn method in the 18th Century for locking pieces of timber together in order to frame a house. This is inside Charles and Sarah Robinson’s antique 1737-built house at 4 Carter St. Credit: Michael Dinan

A neighbor in Silvermine, Brett Wilson, noted that the prior barn on the Robinsons’ property “could not have been restored” and said he was confident that the family would do a “beautiful job” of replacing it.

Tom Nissley, a local Realtor who told the ZBA members he was speaking not only for himself but also as a representative of the New Canaan Historical Society, New Canaan Preservation Alliance, Barns Project and Connecticut Trust for Historical Preservation said the house is located “a very, very key corner entrance into New Canaan where Carter Street meets 106.”

“Probably that was an Indian trail before it was a road, and certainly the location by itself represents the rural nature of the origins of New Canaan. And what they [the Robinsons] have done to preserve the house is referred to everyone as the model of what can be done and should be done to do historic preservation, and that same thing is true of this barn.”

Looking north from the New Canaan Mounted Troop property at 4 Carter St. before the deteriorating and unsalvageable barn there was taken down.

According to a section of the “Landmarks of New Canaan” book from the Historical Society (and available in the nonprofit organization’s research library up on God’s Acre), the house was built in 1737 (it likely took years to build) by Lindal Fitch, whose grandfather John had been an early settler of the Norwalk Colony.

“He designed a house which would be sociable to live in and which would be beautiful both in the lines of its structure and in the details of its decoration,” according to the “Landmarks” article by Margaret Cabell Self.

“The great central chimney provided a huge fireplace in the kitchen and smaller ones in each of the downstairs rooms. As these were the days before stoves a broad hearth was necessary and a good Dutch oven for the baking. But the kitchen was not used just for cooking, it was the living room, the social meeting place for the family as well. So Lindal’s kitchen faced east and was by far the largest room in the house, running, as it does, the full width of the house. The kitchen door opened to the south and the well is close by, thus, in winter, those going outside for water or wood were well protected from the icy blasts from the north by the mass of the house itself.”

A wider view looking roughly North-Northwest past the proposed barn site to the Robinsons’ saltbox home. The original 1737 structure is on the left, and the family used materials as closely resembling the original timber as possible to create its more modern addition off of the back—an example of historic preservation widely heralded by local experts. Credit: Michael Dinan

The Robinsons have preserved that kitchen area while also creating a “consonant” modern addition off of the back that includes living space and a master bedroom.

Standing by the well that Self referred to in her piece for the “Landmarks” book, Charles explained that, as with the addition, he and Sarah are seeking to do the very best job with the barn in creating a structure that “thematically and structurally” harmonizes with the house.

“Albeit a separate building, we are going to try to do with [the Hancock barn] what we did with this addition, which is to tie it as closely as possible, and in as many ways as possible, to the original house.”