George McEvoy sidles on a recent morning into a well-worn, straight-backed faux leather chair, crisscrossed with duct tape and positioned before the potter’s wheel here in a cramped room just off of his long-ago converted Seminary Street garage.

New Canaan resident George McEvoy, a retired marketer and active potter, in his workshop/studio on Seminary Street. Credit: Michael Dinan

One step away—that is, halfway across the room—a microwave for heating coffee sits on a shelf that’s splattered with clay, as are sheets of burlap and tarp that surround the wheel itself. Shaping and trimming tools hang from a wood plank nailed into the wall that’s also adorned with postcards, photos and Modigliani prints.

“When I started, I just said I enjoy doing it and I could sit at the wheel for an hour or two and you’d think 15 minutes go by, you’re concentrating on it,” said McEvoy—strong clear voice, sharp mind, nimble body and thick silver hair defying his 74 years. “You lose your mind into it.”

McEvoy’s studio is located out back of the very distinctive home he shares with wife, Heidi, on Seminary Street in New Canaan. Credit: Michael Dinan

A New Canaan resident for 45 years who has lived for half that time in the yellow Victorian home with the turret on Seminary—the one just below the crest of the hill there, with the trumpet vine tree weaving into the house itself— McEvoy first “lost his mind” to pottery in 1962.

At that time, he was just embarking on a career in marketing, and still four years shy of meeting Heidi, the woman he’d marry in 1967 and with whom he’d have two children, Kate and Colin, before the decade was out.

George Fintan McEvoy Stoneware Pottery, New Canaan. Credit: Michael Dinan

And as the McEvoys raised their kids and George himself launched a business out of his home many years before that became common practice (he had an original Mac and dot matrix printer), the introductory pottery classes he tried on a whim as a young man evolved into something that transcended mere hobby.

Sitting at the same wheel he’s had since moving to Seminary Street, creating bowls, vases, sushi plates, teapots and ornamental pottery, much of it in a traditional Japanese method and style, McEvoy finds creative outlet and expression, connection to history, peace of mind and—in ways that even surprised him when George Fintan McEvoy Stoneware Pottery was launched—a nice bit of business.

Here’s a slideshow featuring some of McEvoy’s work—to pause and see what he says about each piece, just put your cursor over the photo. Article continues below:

[acx_slideshow name=”George Fintan McEvoy Stoneware Pottery”]

‘In grammar school, I pretended to be sick and stay home’

McEvoy grew up in Old Greenwich, the only child of a mother who divorced when he was very young. They lived with her parents and McEvoy credits his maternal grandfather, William Beers, as the greatest influence on him in his creative endeavors as a boy.

George McEvoy, with ‘Grandpa Beers’ in Old Greenwich, ca. 1942. Contributed photo

A tool and dye maker with Yale & Towne in neighboring Stamford, Beers “was very handy” and had his own workshop at home, McEvoy recalled.

“Also I helped him, I was very young but he built a boat in the basement, and I helped him do that when I was 10 or 12 years old, so that was working with my hands,” McEvoy recalled. He enjoyed that creative work at home far more than he did in school, where he’d pretend to be sick just to get out of art class.

He graduated from Greenwich High School in 1957, then earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology from the University of Connecticut—a curriculum that included one course, “Methods in Social Research,” which dealt with public opinion polling, that McEvoy credits with having the most direct influence on his business career.

George and cousin Bill Beers with ‘Grandpa Beers’ in Old Greenwich, ca. 1943. Contributed photo

After taking a MBA from The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, McEvoy in the fall of 1961 joined the U.S. Army Reserve.

“A friend of mine said, ‘You better join the Reserves, because things are heating up in Vietnam and unless you want to be a foot soldier or get married and have a kid in a hurry, join the reserves,’ ” McEvoy recalled.

He did six months of active duty and then, living in an apartment overlooking Greenwich Harbor, found a job with a consulting firm on King Street in Greenwich. Single and working at a time when even the bosses left the office at 5:30 p.m., McEvoy recalled that friend of his, Dick Montross, had majored in ceramics in college and this was in his head when he saw an ad one day in The Village Voice. It offered 10 pottery lessons for $25, at a studio just on the other side of Cooper Square in Manhattan’s Lower East Side (Bob Dylan getting his start nearby).

George (foreground) in Old Greenwich. Contributed photo

“Something said, ‘Hey, give it a try,’ ” McEvoy recalled.

He was a natural from the start. Sitting at a potter’s wheel for the very first time, in view of McSorley’s Old Ale House across the street (the classes were given by two women with training from the Rhode Island School of Design), McEvoy created a bowl “and the woman who was the teacher said, ‘Oh, where did you study before you came here?’ ” he recalled.

“And I said, ‘God’s honest truth, this is the first time I have ever touched a piece of clay in my life,’ and she said, ‘Oh, come on you’re putting me on.’ So for some reason I took to it from the get-go.”

‘You’ve got to get the touch’

Kate and George, ca. 1976. Contributed photo

To that point, dabbling in amateur photography marked the extent of McEvoy’s creative endeavors. He had a friend in Riverside with a dark room in his house that he could use.

About one year after the first class, McEvoy “got the bug for pottery” and sold off his dark room equipment to buy a pottery wheel—a “kick” wheel as opposed to an electrically powered machine.

“I was learning the basic skills of how to shape a piece, how to make something tall as opposed to how to how to make something bowl-like, or like with some pieces where you have to put different pieces together to make something,” McEvoy said. “And it just that’s basically requires a lot of practice. You’ve got to get the touch. It’s feeling how thick the clay is, how wet it is.”

George and Colin, hiking in Arizona ca. 2007. Contributed photo

The New York City lessons under his belt, McEvoy soon discovered the Clay Arts Center just over the state line in Port Chester, N.Y., and there he met a man, the late Henry Okamoto, whom he describes as his most important teacher in pottery.

The center not only supplied lessons, clay and tools for creating pottery, but also “fired” (in a kiln) its students’ work to completion.

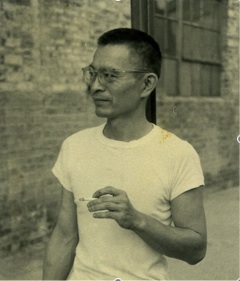

Henry Okamoto. Contributed photo

While he was taking lessons at the center, McEvoy—who now owns a piece of pottery that’s about 2,500 years old—developed a sense of the art form’s deep history. Okamoto, in particular, school McEvoy in Asian techniques of creating simple forms and allow glaze variations to tell a story.

“The older I get, the more the history means to me,” McEvoy said.

At Clay, McEvoy recalled, he was only seeking to create a piece that he’d be happy with.

Heidi McEvoy in Portugal, 2013. Contributed photo

“I remember the first time at the place in Port Chester where we fired the pieces, I remember one time they opened up the kiln and they put the finished work out on the table and I picked up a piece and said, ‘Oh this is really a nice bowl,’ and then I realized it was mine,” he recalled. “Wow.”

‘I can’t draw to save my life’

In about 1965, while working his first job up on King Street, McEvoy met his would-be wife, Heidi. They married the following year and in 1967, daughter Kate was born, followed two years later by the birth of their second child, a son they named Colin.

George and Kate in Switzerland, ca. 1985. Contributed photo

They’d been living in the Turn of River section of Stamford ($125 a month rent for an entire house, garage included) after getting married, and when Colin was about six months old, the family moved to Brinckerhoff Avenue in New Canaan.

Here in town, the kids attended South School and Saxe Middle School—Kate would graduate from New Canaan High School and Colin from King Low Heywood Thomas private school ($4,000 back then).

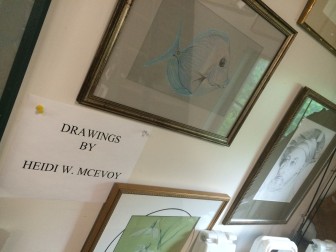

In their home, Heidi—an artist and musician whose framed drawings line the walls of McEvoy’s studio, and whose collection of baskets hang from the ceiling there—taught the kids to play piano while both parents became involved in the community in their own ways. Kate took up violin, Colin the French horn (and racquet sports).

Heidi McEvoy’s drawings adorn the walls at the pottery studio in New Canaan. Credit: Michael Dinan

Eventually, when the kids were older, McEvoy for five years led a movie discussion group out of New Canaan Library, and started mentoring kids in Norwalk Public Schools.

For seven years, he serves as president of the newly defunct Waveny Chamber Music Society, which put on four professional concerts each year at the Carriage Barn Arts Center.

The pottery has been all his own.

“[Heidi] doesn’t like the touch of clay, and I can’t draw to save myself,” McEvoy said. “Nor can I play an instrument.”

‘It’s in the hands of the gods’

Yet, while his kids were in school and McEvoy was working for others, he often couldn’t find as much time for pottery as he would have liked.

The “ingredients” of George McEvoy’s glazes in containers on shelves in his home pottery studio. Credit: Michael Dinan

He had a makeshift workshop set up in the basement on Brinckerhoff, complete with an electrical potter’s wheel, and spent as much time down there as he could, creating perhaps 50 to 100 pieces per year.

“The higher up I got [at work], the more time I had to spend working for others. There was not a lot of free time,” McEvoy recalled. “I never lost touch with the pottery, but there were periods of time in terms of more than one year when I couldn’t spend much time on it because I needed to work.”

That all changed when Kate went off to college and Colin was finishing up high school, and McEvoy underwent a layoff at his job.

While thinking about his next move in terms of full-time work, McEvoy began moonlighting as a marketer, and soon found himself making as much money as he did while working for someone else. So, he set up his own company.

George McEvoy installed a kiln on his property in New Canaan. Credit: Michael Dinan

“For the first six months that I had my business, I would walk into town to get a coffee or something and I’d see people and they would say ‘Hey George, you got the day off or something?’ ” McEvoy recalled. “It wasn’t as common back then to work for yourself. I didn’t want to tell people about it, was embarrassed or something. And it turned out to be the smartest thing I ever did.”

In part, that’s because he now had more time to pursue pottery, creating say 500 pieces per year—and by now, he and Heidi were settling into Seminary Street and his work was selling.

He had an electric heater set up in the small room off the garage so that his clay wouldn’t freeze in winter. McEvoy also had a propane-fired kiln installed in a shed out behind his garage, so he could complete his work from start to finish (sculpting, firing, glazing).

“When I first started making pottery and was making it for a couple of years, I still had no thought of selling it, I was just making it because I liked doing it and when then somebody said, ‘You should sell this stuff,’ ” McEvoy recalled.

A vase made in traditional Japanese style, by George McEvoy. Credit: Michael Dinan

“I said, ‘Ah bullshit nobody is going to buy this work.’ And somebody told me about a place in Hamden, which was called Current Crafts, and I went up with a couple of boxes, and the guy there, he was interesting—he bought the work on the spot and he paid you. Most places you take it and leave and when it sells you get 50 percent. So, he bought some and I was like, ‘Eureka, this is fantastic,’ so I started having a show here in my studio every year, at Christmas time.”

A jar with an exotic wooden lid. Pottery by George McEvoy. Credit: Michael Dinan

He also sold his pieces for a while out of craft shop in Nyack, N.Y., just over the Tappan Zee. Today, enough people know of McEvoy and his work that they contact him if they’re looking for items such as a wedding or birthday gift. He also continues to show sporadically, such as at a recent New Canaan Farmers Market at the Center School lot.

McEvoy said he’s been “officially” retired for about 10 years. Looking back, what would emerge as important parts of his life came on unexpectedly, McEvoy said, including his foray into pottery, working for himself and moving to New Canaan.

Asked whether he considers himself a planner by nature, McEvoy answered: “I would say that when need be, I can be very organized.”

He added: “When it’s in the kiln, it’s in the hands of the gods.”

George Fintan McEvoy Stoneware Pottery at 66 Seminary St. can be reached at 203-912-1634 and gmcevoy@optonline.net.

Can you tell me the name of the ceramic teacher in 1972? MORLY? First and last name please.

Myldred Marcely known as “My” was the ceramic teacher at NCHS.