Saying they wanted to support a New Canaan couple’s efforts to preserve a historic 18th Century home that narrowly avoided the wrecking ball this past summer, planning officials last week took the unusual step of OK’ing a sign to be planted out front of the property on condition that it’s a different color than originally presented.

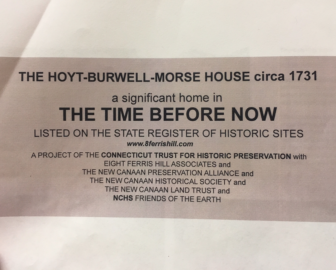

Proposed sign to be set out front of 8 Ferris Hill Road.

Despite concerns that the sign to be installed at 8 Ferris Hill Road (in the manner of a demolition sign) also is too large—and strong feelings about the specific language chosen for it—members of the Planning & Zoning unanimously approved it at their regular meeting Tuesday.

The sign “is just too big and the color seems wholly inconsistent with the historic house,” P&Z commissioner John Kriz said during the meeting, held at Town Hall.

“It’s Barbie pink.”

Homeowner Tom Nissley, who with his wife acquired the home and 2.14-acre property for $1.5 million in June, tax records show, explained that the intention is to have the color of the sign match the shingles on the house.

“I had to try to reproduce a color that doesn’t exist on the computer and that is how you got this color,” Nissley said.

The lettering on the sign is to read:

The Hoyt-Burwell-Morse House circa 1731

A significant home in

The Time Before Now

Listed on the State Register of Historic Sites

A Project of the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation with

Eight Ferris Hill Associates and

The New Canaan Preservation Alliance and

The New Canaan Historical Society and

The New Canaan Land Trust and

NCHS Friends of the Earth

The 1735-built farmhouse, a classic saltbox structure, has “a tremendous amount of history is rolled into it,” Nissley said.

“The people who lived in it, way before there was a town of New Canaan. Way before there was a United States of America. It was essentially part of Norwalk.” (See fuller history below.)

Explaining how the idea for this sign came about at all, Nissley said that at the time he purchased the home from its prior owner, a ‘ Notice of Intent To Demolish’ signboard had been planted outside the house.

“And we took down the demolition sign and said, ‘That’s a beautiful signboard, couldn’t we at least for a temporary period put up a sign that said ‘Saved’ or something?’ ” Nissley recalled. “And then we thought that was a bit dramatic, but I have put before you the sign that we would like to put up, which identifies it as the Hoyt-Burwell-Morse house and the significance of it in what we are calling ‘The Time Before Now.’ ”

The phrase sat uneasily with some on P&Z. Commissioner Claire Tiscornia said it may work better to promote the home’s historic significance rather than use the phrasing.

“It almost looks like an advertisement for something,” she said. “A movie or something.”

Kriz said the rest of the wording on the sign was OK but did not care for ‘The Time Before Now’ and especially was averse to its large lettering.

It is “the largest typeface in it,” Kriz said. “It perplexes me.”

Nissley said he was open to suggestions on the wording. P&Z Secretary Jean Grzelecki, chairing the meeting in the absence of Chairman John Goodwin (away on business), said that “on no signs in New Canaan can we control the content.”

Grzelecki said: “Frankly this is not a sign we would ever approve if there were not extenuating circumstances, I think that is fair to say, because it is large. However, having said that, this is a significant house in New Canaan’s history and the fact that it was saved—and anybody who knows the story of how this came about, it really was quite an involved thing—it was a very near thing that it very easily could have been demolished, so there was a certain amount of gratitude that this thing was rescued. And I am probably as picky about signs as anybody in New Canaan. I am OK with this for this type of a circumstance.”

Commissioners asked whether the state agency that oversees historic designations provides signs (yes but a smaller, different one, to be affixed to the structure itself), whether the sign would match the color the of the fence out front (it’s pretty close), whether neighbors had been notified about it (no but the only one who can see the sign from her home likes it) and whether he himself is living at the house or plans to (no).

P&Z commissioner Elizabeth DeLuca, who sits on the group’s sign committee, asked whether the proposed sign would be temporary.

Nissley said he estimated it would be in place for two years “while we are going to be renting part of the house but we are also going to be trying to use a portion of the house as a living museum.”

“The easement that has been put on it requires that maybe twice a year it be open for the public but we are really talking about more,” Nissley said. “But it is not our intention—in fact, it would be nuts—to try and have that sign there forever.”

Much of the home’s history has been included on an application that went into the Connecticut Commission on Culture and Tourism to include the home on the CT State Register of Historic Places called it significant “for its contribution to the settlement of New Canaan, Connecticut.”

The application said: “According to a history written in 1947, the land upon which the home stands was a portion of a large division belonging to the sons and nephews of Joseph Hoyt,” the application said. “This tract included approximately all of the Canoe Hill road from where it leaves Carter Street, East, West, and North into Laurel Road.

“The Hoyts represent the beginning of a movement to resist the long commute from Norwalk or Stamford for church services. To cut down on travel time, a congregation was organized and named Canaan Parish. “The town of New Canaan grew from this congregation and was chartered in 1889. The New Canaan Historical Society’s survey suggests that there are only six other residences built before the Hoyt-Burwell-Morse House that are still standing. A generation of Hoyts built their homes along the ridge where the Hoyt-Burwell-Morse House now sits on and it became known as ‘House Ridge.’ This home is all that is left to show of this settlement and movement.

“Between the creation of the home and the town’s establishment, the house was occupied by several noteworthy families, mostly descendants of the first settlers of ‘House Ridge.’ These settlers had significant names to the successful creation of New Canaan such as, the Hoyts, the Benedicts, the Burwells, Carters and the Steven. Many of these names are tied to key social, political or economic leaders for the growing area. Some were founders of the Canaan Parish, soldiers, pioneers or businessmen.

“A town historian also believes the house was once occupied by Onesimus Comstock, a man born into slavery in New Canaan in 1761 and said by some to be the last living slave in Connecticut. Comstock had identified himself as a “voluntary slave” in the 1850 census for Norwalk and is buried in the nearby Canoe Hill Cemetery. He died at age 97 in 1857.

“The home continued to house the town’s significant families well beyond the time the town was chartered in 1889. This can be seen even in the landscape surrounding the home. Gilbert Birdsall, who owned the third avenue street railway line in New York purchased the house for his daughter upon marrying Franklin Stevens and the two planted sugar maples in the front yard which can still be seen. These were called ‘Bridal Maples’ and were commonly planted when a young couple went to live in their new home.”