New Canaan resident Buzz Kanter purchased his first antique motorcycle around 1986—a BSA M20, from a man selling three of the classic World War II bikes in the pit of a racetrack in New Hampshire.

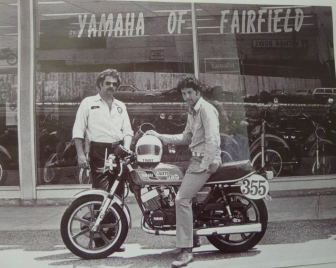

“1978 on my 1977 Yamaha RD400 racebike with my sponsor – Yamaha of Fairfield (CT).”— Buzz Kanter

Though only in his early-30s at the time, the Stamford native already was a veteran of New England’s motorcycle scene and circuit.

A decade earlier, Kanter had walked away from high-speed racing following an accident on a track in Bridgehampton, N.Y.: A fellow racer, who would spend six months in hospital, crashed into him as they headed into a corner at 130 mph.

Buzz Kanter with his 1930s English JAP motorcycle, one of three bikes he owns that will be featured as part of the “Va Va Vroom! The Art of the Vehicle” exhibition, opening Sunday at Carriage Barn Arts Center. Credit: Michael Dinan

“I finished the season and said, ‘I’m done,’ ” Kanter, 60, recalled Thursday morning from the gallery at Carriage Barn Arts Center, standing near one of the vintage motorcycles he has acquired since that day in 1986. “And I started playing with antique bikes. I found a romance and attraction to them. The romance of chuffing down the road rather than screaming down the road.”

On Sunday, three of Kanter’s motorcycles—a 1930s English “JAP” speedway bike (“a very fast, light, skeletal bike that only turns left, can do close to 100 mph and has no brakes or transmission—just a throttle, clutch and kill button”), ’66 single-cylinder Ducati and 1947 Indian Chief (made in Springfield, Mass.)—will quite literally “take the stage” at the Carriage Barn during the opening reception of a widely anticipated show that celebrates motor vehicles.

Carriage Barn Arts Center co-directors Arianne Kolb and Eleanor Flatow are gearing (sorry) up for “Va Va Vroom! The Art of the Vehicle” which opens Sunday. Credit: Michael Dinan

“Va Va Vroom! The Art of the Vehicle” will run April 19 to June 14, with the correlating Monaco Grand Prix Fundraiser (tickets here) scheduled for 7 p.m. on May 16. Featuring contemporary paintings, drawings, photographs and sculptures by 35 artists from Connecticut and New York as well as vintage advertising posters, motorcycles and car models, the show celebrates the 1895-built Carriage Barn’s own heritage as the Lapham family’s garage for horses, carriages and cars.

Brainchild of the Carriage Barn Art Center’s co-directors, Eleanor Flatow and Arianne Kolb—and the pair credit Caffeine & Carburetors founder Doug Zumbach for his generous help—Va Va Vroom appealed to Kanter, in part, because he’s “proud to support anything that promotes motorcycling in a positive light.”

“Rebuilding my 1915 Harley before the 2010 Motorcycle Cannonball.”—Buzz Kanter

Flatow and Kolb said they were introduced to Kanter by Zumbach (“He said, ‘Buzz is the man,’ ” Kolb recalled) and see the motorcycles as works of art on the same level as the fine art that forms the exhibition.

“We are trying to highlight the history of vehicles in New Canaan, incorporating that into the town history, the art show with local artists and contemporary art work, as well as vintage posters,” Flatow said. “We are trying to tell a story, as we always do.”

“Getting arrested for riding too slow on my 1915 Harley before the Motorcycle Cannonball in 2010.”—Buzz Kanter

Kanter tells a good story himself.

Though it isn’t clear just how many motorcycles Kanter owns—his response when asked was: “I have more than a dozen and less than Jay Leno”—the bikes are far more than a hobbyist’s cold “collection” to the town resident, a 2002 inductee into the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame. As working machines that he rides on a regular basis—locally, regionally and even coast-to-coast, for weeks at a time—motorcycles are a passion for Kanter, and they’ve seen him carve out a singular career in publishing.

“With Betty Boop at the Stamford Parade some years ago on my 1955 Harley Panhead and sidecar.”—Buzz Kanter

It started in 1969, the year Kanter’s family moved back to Stamford after six years living abroad, in England. Kanter entered ninth grade at The King School (he would take a New Canaan girl to prom, an early connection to the town) and his parents allowed their four boys to have a Honda mini-bike. The Kanter parents told the boys they’d never ride motorcycles, and they were right—for a few years.

“My 1931 Indian 101 Scout in front of the Summer St. Stamford office of American Iron Magazine and Motorcycle Rides & Culture.”—Buzz Kanter

Kanter entered the University of Connecticut and, while working toward a dual bachelor’s degree in sociology and psychology, began buying and riding increasingly fast motorcycles.

His family’s business, including the Penny Press (named for his mom, Penny Kanter), was magazine publishing—puzzle magazines. When he graduated, still nursing his growing passion in bikes, Kanter entered the field by working for a magazine distribution company, and after a little more than one year, joined the family business on the circulation side.

“Posing in costume with my friend and motorcycle designer Craig Vetter at the Mid Ohio racetrack several years ago.”—Buzz Kanter

He began to pursue a master’s degree in communication at Fairfield University, but dropped it about two-thirds of the way through and ultimately took a MBA from the University of New Haven, launching his first magazine as part of his thesis (called “Old Bike Journal,” it consisted mostly of classified ads for selling old bikes and parts).

Kanter put out some 50,000 copies of that first issue, launching his own publication company on its back, and in late 1990, left the Penny Press to focus on his own magazine. The following year, now married (he and his wife, Gail, have two teenage girls who attended West and Saxe), he bought a small Harley publication in California called “American Iron” that had been failing.

A recent cover of “Motorcycle: Rides & Culture” magazine.

Living in North Stamford, Kanter bet everything that he could get the magazine to run-rate profitability within eight months, risking personal bankruptcy. He and Gail (who appeared on the first cover, with that same BSA M20 from New Hampshire) shifted the focus on the magazine toward something more serious than topless girls on motorbikes (“we focus on the tin not the skin” was his motto), made a small profit and has been profitable ever since.

Now CEO, Publisher and Editor-In-Chief of Stamford-based TAM Communications, Inc, Kanter puts out multiple motorcycle magazines. Titles have included “American Iron Magazine,” “Roadbike” magazine, “Classic American Iron Magazine,” “Thunder Alley,” “Hottest Custom Iron,” “90 Years of Harley Davidson” and “Motorcycle Tour and Cruiser.”

“Me kickstarting my 1937 Indian Sport Scout racer at New Hampshire International Raceway last year.”—Buzz Kanter

“It’s more than a career,” said Kanter, a New Canaan resident for nine years who also sits on the Board of Finance. “It’s a lifestyle, it really is. When I am not working, I’m in the garage work on my bikes. I’m using them. I’m having fun. It’s not just for publication or filler for the magazines. It’s a passion of mine.”

That passion has fueled Kanter’s desire to race, tour and show steadily, year-in and year-out. For the past few years, and perhaps again next summer, Kanter has participated in a unique type of race called the “Motorcycle Cannonball.” It was, he said, “started in 2010 by a group of fringe lunatics who are into very, very early motorcycles.”

“Yes, I do ride year round if the roads allow. Me and my 1936 Harley EL Knucklehead.”—Buzz Kanter

Restricting the vehicles involved to vintage bikes—for example, in its first year, no motorcycle newer than 1915 could be used—the participants set out on a cross-country trek, using no highways and no GPS, and scoring points for getting from A to B (they ride about 300 miles per day) with no breakdowns or help, and not arriving too early or too late to the day’s destination.

“In downtown New Canaan on a New Year’s Day ride with Town Council member Roger Williams. I was on my 1936 Harley, Roger on a new BMW motorcycle.”—Buzz Kanter

“I remember at the beginning I knew about half the [approximately 45] riders, and talking about it in the beginning and I imagined we were like Christopher Columbus getting ready to leave. We were pretty sure the earth was round.”

The 2012 race from New York to San Francisco allowed bikes up to 1929, and last summer Kanter rode a 1936 Harley, crossing the Continental Divide three times, riding through Loveland Pass, Col. (Kanter damaged his rotator cuffs, likely from the severe riding last summer, and is recovering now from “offseason” surgery.)

“Left to right – Buzz Kante on 1929 Harley, Paul Ousey on 1925 Harley JE, Jim Petty on 1927 Indian Chief. On our ride across the US on the 2012 Motorcycle Cannonball – NY to San Francisco.”—Buzz Kanter

Asked whether the Motorcycle Cannonball was as romatic as it sounded, Kanter said, “I wish it were more romantic. I think it is more romantic telling story after the fact, but it’s hard work.”

His wife Gail does not join him on the trips (“She’s staying at home—she’s smarter than I am”) and there’s often no cell service along the road.

“The day before the first Motorcycle Cannonball in 2010.”—Buzz Kanter

“My feeling is, as difficult as an event like Motorcycle Cannonball was—and it was: physically, emotionally and financially—it’s a real challenge. As much of a challenge as it is, I seldom have felt so alive. I mean, it’s you against everything else. You against the roads. You’ve got pouring rain, lightning, hail and sleet.”

He added: “My feeling is that I am never going to be younger. I don’t want to wake up and say, ‘Geez, I wish I had done X.’ So I am doing it. I’m not driven that I have to do it, but I enjoy these things.”

A recent cover of “American Iron” magazine.

And he enjoys doing them here in the United States. Asked whether he’d ever considered touring Europe on a motorbike, Kanter quickly said “No.”

“I’ve got a love affair with our own country,” he said. “And every time I ride across it on an antique motorcycle or any other way, I rediscover it.”