Editor’s Note: This is the middle installment of a three-part series. The other two parts can be found here:

- Heroin and New Canaan, Part 1 of 3: Tracing and Defining a Problem

- Heroin and New Canaan, Part 3 of 3: ‘Reach Out to a Person’

Nancy Welch moved to New Canaan 10 years ago with her husband and three kids.

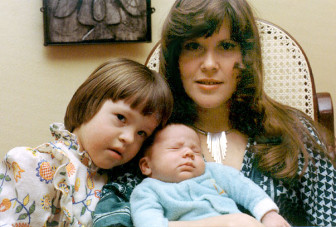

“At one month old, Ian was such a beautiful baby. He was perfect. I felt so blessed.” —Ginger Katz with her son, Ian. Photo published with permission from Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

With one child now at each level in New Canaan Public Schools, Welch said she has become increasingly concerned about what officials are calling a rise in recent years of heroin’s availability and use in New Canaan and the region.

“My concern would be that one dose of it can kill you,” Welch told NewCanaanite.com when asked for her thoughts on the drug’s prevalence here.

“I think a lot of parents don’t know about it,” she added. “Parents don’t necessarily know what to look for.”

“Candace was six when her little brother was born. She loved him right away.” Published with permission from Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

Welch is right on all counts, officials say, and there are local experts who can provide information to and answer questions for parents. They include physicians, school, police and human services providers in New Canaan, who for years have offered our youth in town counseling, assistance, shelter and—of critical importance, experts say—relationships with trusted adults.

“The inexpensive, easy access that we have seen in heroin across the board certainly has escalated its use among kids. It’s scary,” said Denise Qualey, managing director of crisis and clinical services at Kids In Crisis. Headquartered in Cos Cob and serving Fairfield County for more than 30 years, Kids in Crisis provides free, around-the-clock crisis counseling and shelter. The organization last year served more than 5,000 children.

“Five-year-old Ian couldn’t wait to tell Santa what he wanted for Christmas. Having big sister Candace right there with him made it even more special.” Published with permission from Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

Kids In Crisis is one organization we’re turning to in this, the second installment in a three-part series that examines heroin and New Canaan. In Part I, we spoke to police, human services providers, school officials and medical experts about just why we’re talking about heroin at all, how kids get the drug and the nature of addiction, as well as efforts from law enforcement to combat its spread. Part III will run Friday.

‘Always Keeping Communication Open’

“I’m not a drug expert or substance abuse specialist, but what I can tell you is that kids are doing different things with heroin today than they did in years past,” Qualey said.

“It’s not just intravenous drug use. They are snorting it. They are doing other things with it, and because it’s readily available and cheap it’s becoming more common. What used to be viewed as the habit of hardcore drug addicts injecting with heroin is not so much what we see now. I think parents would be alarmed to know how exposed their kids are to these things.”

“It was a beautiful summer day and Ian’s smile was as bright as the sunshine.” Published with permission from Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

Yet there are strategies for parents, Qualey said.

“It’s always looking for warning signs. It’s always keeping communication open. It’s talking,” she said.

“Your kids need to have trusted adults in their lives and we need to listen to those adults, and kids need to have access to trusted adults,” she said.

Parents should be aware of changes in their kids, Qualey said: Friends, sleeping, eating, school performance, “a lack of interest in hobbies and things that they used to love that they no longer love.”

All of the above are warning signs.

“You really need to know what your kids are doing have a relationship with them that’s got a flow of communication,” she said.

“First Communion at St. Thomas the Apostle church. Ian was seven. Thirteen years later, I would do the first Courage To Speak presentation to the community from this church at the invitation of Father Murphy.” Published with permission from Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

“And as they get older, you do need to trust your kids, but parenting doesn’t end in high school,” she added. “I think a lot of parents think, ‘Oh, high school is a time when they want to be separate from the parents and be independent.’ And I agree with natural growth and kids becoming independent, but you still have to supervise, check in on and follow up with them.”

‘I Don’t Care How Much Work Parents Have’

Ginger Katz of Norwalk lost her son to a heroin overdose in 1996. He was 20. The photographs interspersed throughout this text are all of Ian, republished here on NewCanaanite.com with Katz’s permission.

Not long after her son died, Katz founded “The Courage to Speak Foundation,” a nonprofit whose mission is, the website says, “Saving lives by educating and empowering youth to be drug free and encouraging parents to talk to their children about the danger of drugs.”

“Leaving for church, Ian was so pleased with how he looked in his new suit.” Published with permission from Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

Katz last year came to New Canaan High School to talk to students—and parents, through her Courageous Parenting 101 program—about her experience as a caregiver who lost her son to addiction and overdose.

It’s critical, Katz said, for parents to start talking to their kids at an early age.

“You have a choice. You talk about it now,” Katz said.

“You constantly talk to your children with love and caring. You don’t do a lecture. You take them to family nights. You talk to them constantly. Not constantly where they’re worn out about it: You get to know them just by going on a car ride with them or by going to the mall and have lunch, and they will open up. Ask them what good things happened and what not-so-good things.”

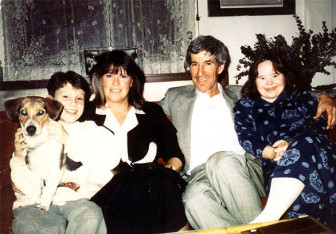

“Cuddling on the couch with Mom, Dad, Candace and our dog Sunny. Ian was ten.” Published with permission from Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

“I don’t care how much work parents have,” she added. “This is a priority. These are life-saving tools.”

Though her son is just six years old, New Canaan resident Maureen Shankar said she already is cognizant of what will face her family as her son gets older and he will face peer and other pressures in town.

Shankar, a resident for seven years, said she is very fond of New Canaan and also recognizes that kids here often are driven and live within what can be a high-pressure environment.

In New Canaan, where many teens experience a certain “roominess” because they may have their own cars and their own rooms at home, youth often experience a certain roominess, said Jacqueline D’Louhy, assistant director of youth services with the town’s Department of Human Services.

“Graduating from Norwalk High School, Ian had a huge smile for his mentor Mr. Amos who was handing him the diploma.” Published with permission from Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

Though unintended, those factors can contribute to a loss in parents’ ability to supervise, she said.

“I just think sometimes there can be a ton of space,” D’Louhy said.

And it’s not always intuitive for teens who are accustomed to heavy programming what to do within that space when there’s a gap in scheduled activities.

“We have kids who have so many activities [that] when they do have downtime, they don’t know what to do with that downtime,” D’Louhy said.

According to Capt. Vincent DeMaio of the New Canaan Police Department, kids in those moments can face serious peer pressures to experiment with drugs, and without understanding the risks.

“The effect [of an opioid such as heroin] could be, you could be in a coma, you could be killed from an overdose,” DeMaio said. “And they also have strong negative effects when paired with alcohol, because alcohol is also a central nervous system depressant. So you’re putting two depressants in your body at the same time. It intensifies the effects.”

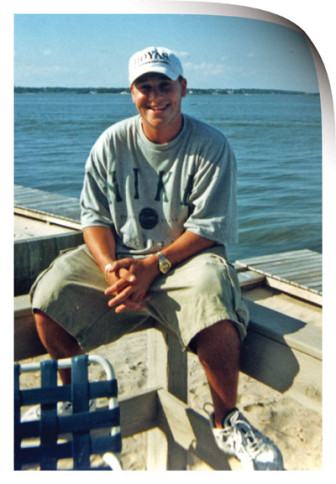

“This is a photo of Ian four weeks before he died while he was working on his recovery.” Published with permission from Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

Echoing some of what Qualey and Katz said, DeMaio urged parents to have an open dialogue with their children, “especially if they suspect that something is wrong.”

“Not wanting to address it can always lead to greater problems,” he said. “You need to have that open discussion with your kids and say ‘Hey you need to be able to come to me and if you’re having a problem, having an issue, we need to get that fixed.’ ”

‘There Is Certainly a Stigma That Doesn’t Attach to Oxycodone’

In a town like New Canaan, part of the difficulty in discussing problems of addiction—in seeking information or help to address heroin use, for example—is the stigma attached to it.

When asked about that stigma, clinical psychiatrist Dr. Eric D. Collins—physician-in-chief at the New Canaan-based psychiatric facility Silver Hill Hospital, and an associate clinical professor at Columbia University—said: “It starts with this—heroin is illegal, period, for any medical or other use.”

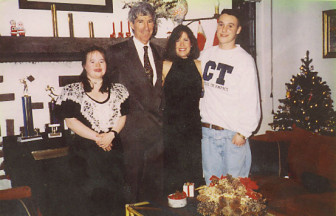

“This was the Christmas of Ian’s first year at college. He was already using cocaine. I didn’t find out until after he died.” Published with permission from Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

“So there is certainly a stigma that doesn’t attach to Oxycodone,” Collins said, noting that it still is illegal to resell Oxycodone or even give it to someone else.

“Heroin has this stigma and parts of our culture for a long time—I think of movies like ‘The French Connection,’ which some of the parents in town are old enough to remember, and all kinds of things like that—make the drug more stigmatized. I guess part of my message is: They [opioids such as heroin and prescribed painkillers] are, pharmacologically, the same.”

As Collins explained in Part I of this series, New Canaan youth who find heroin likely came to it through an addiction to painkillers, which they may have found in their parents’ medicine cabinet.

” ‘Mom, I’m always going to have a beer with my friends,’ Ian told me that last summer. ‘If you do, you’ll go back to the drugs,’ I said, but he couldn’t see that. He really did stay clean that summer. For a while, he was the Ian I used to know. For three months, I had my son back.” Published with permission from Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

Collins’ message to parents is: “Lock up everything that is unused, and dispose of it. Lock it up and hide the key. If nobody is using it, don’t leave it in the medicine cabinet for somebody to come along.”

One way that prescription drugs find their way onto the black market here, he said, is that workers in our homes—say, members of a house painting crew—will look in our medicine cabinets and pocket what they find.

For people who have unused prescription drugs at home: There’s also a drug drop-off box in the lobby at New Canaan Police headquarters on South Avenue—see the section “Medication Disposal Program” on this page—and April 26 is National Take-Back Initiative Day, now a Drug Enforcement Administration-run program where residents will be provided a convenient way to dispose of medication. We will review this and other resources for New Canaan residents in Part III of the series, running Friday.

“He hung around with Glenn that last summer. With clean kids, non-users. He really was trying so hard, but the drugs were stronger than he was.” Published with permission of Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

‘It’s a Business Choice’

From a high-level view, heroin comes to a community such as New Canaan from a long distance, with poppies grown in a field somewhere—Pakistan or Afghanistan, say. Compared to something like wheat, the drug returns a high revenue yield for its growers, Collins said, and those growers go through some trouble to convert the crop—a poppy primarily is morphine and codeine—into heroin.

The reason it’s converted to heroin specifically is that it’s a more concentrated form of morphine, so it’s more economical for transport, Collins said.

“It’s a business choice,” he said. “For transport you get three times the street value for every kilo or whatever unit of measurement you want to use. In other words, you get a lot more bang for your buck in transport if you convert.”

Once it arrives here—often transported up from New York City and distributed through Norwalk or Stamford, DeMaio said—the drug is relatively cheap (when compared to black market opioid painkillers such as OxyContin or Oxycodone).

Another part of what may contribute to the stigma attached to heroin is that people still have an idea in their heads that it is injected, Collins said.

“So that probably adds to, ‘It’s that much more far afield from usual behaviors’ [way of thinking],” he said.

The drug is largely snorted now, not injected—and that in part is why the heroin, in powder form, often is more potent or “pure” today that it was in the past, Collins said. First, drug users moved away from needles somewhat following the epidemic of AIDS that came in the 1980s. Then, because drug dealers wanted to have a market for heroin, they had to increase the purity of heroin so that it “gave a meaningful effect,” he said.

“It used to be the percentage of heroin in a bag of heroin was very low, single-digit percents,” he said. “And now it’s anywhere from 40 to sometimes 80 percent range. And that’s supply and demand. Supply went up when demand went down. “

“Jason took this picture. It was everybody’s favorite shot. All of Ian’s friends have it hanging in their rooms.” Published with permission from Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

The purity of the drug is a contributing factor to heroin deaths, he said.

In New Canaan, he said, young people likely start with drugs they find at home and it’s only people who got addicted to those who move onto heroin—a contributing factor to its stigma, too.

“You will only see addicted people using heroin, pretty much,” Collins said. “Except if there is a tragic death and there probably will be at some point, I am sad to say.”

‘God Knows I Went to Hell and Back to Save Him’

A 2009 New Canaan High School graduate died of a heroin overdose in neighboring Wilton last October. (Statistically, at least in 2013, New Canaan had no accidental deaths by heroin intoxication, though officials say people here have overdosed on the drug.)

Katz said it’s important for New Canaan parents whose kids already are developing or are suffering with addictions not to blame themselves for their child’s addiction.

“It’s not a reflection on your parenting,” she said.

“This was taken at a friend’s house two days before he died.” Published with permission from Ginger Katz, Courage to Speak, http://www.couragetospeak.org/” credit=”

“I have a pretty good ego and pretty good elf-esteem. I, believe it or not, do not blame myself for my son’s addiction. God knows I went to hell and back to save him. I never questioned what messages I tried to give him. I wasn’t a perfect parent, but I have to tell you, I was very much like every other parent who watches their games, I was proud of him and did everything I could. When I saw him acting out with marijuana, I brought him to counseling.”

Her son, Ian James Eaccarino, lost his battle with addiction, “and I lost him,” she said.

“I don’t want you to be ashamed if your child is using,” she said. “The first try is a mistake. The second one is using. I don’t want you to be ashamed or think it’s a reflection of your parenting. Dealers are targeting our children. As parents, we are not equipped for this. There are no guarantees on whether they are going to take the right or left turn when they come to it, and if they take the wrong turn, you cannot blame yourself. Here’s why: It will stifle you from helping your child. The guilt will get in the way and you will blame yourself. You have to put your child first, forget about the ego. Forget about that. Don’t shove a little sip of beer or pot under the rug.”

Part III of this series will run Friday.